The Two Minute Intro

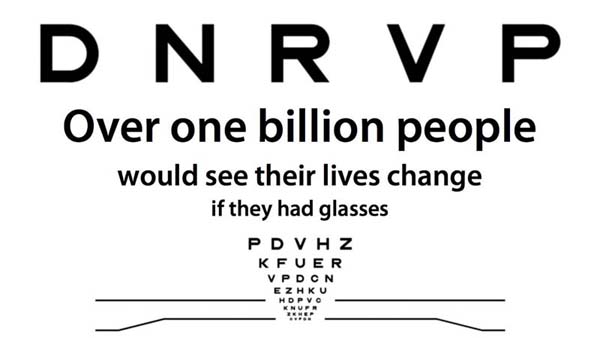

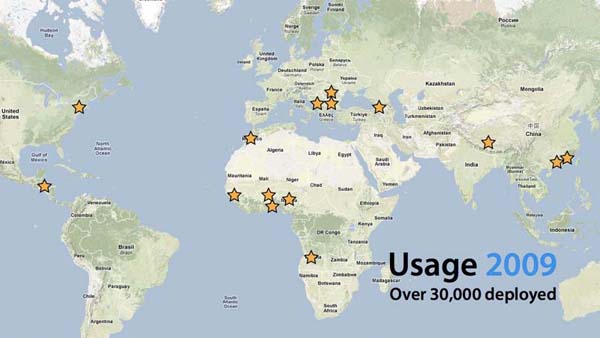

The Centre for Vision in the Developing World believes everyone, no matter where they are in the world, should be able to see. Over a billion people, according to the World Health Organization, would benefit from glasses but do not have access to them. But this is not an unsolvable problem. In this short series of slides, we'll introduce the problem, a solution, and ourselves.

1/13

The Problem

Millions of people all over the world wear corrective spectacles. Chances are that you do, or will have to in the future for reading and close work. But what if you did not have access to them, due to the cost or the lack of trained opticians who can determine the level of correction you need?

For over one billion people in the developing world, glasses are a distant dream. Access to eyecare is almost non-existent in sub-Saharan Africa, and highly restricted in other parts of the developing world. It is beyond the reach of hundreds of millions of the world's growing urban poor.

A lack of proper eyesight has direct effects for those affected by it; a reduction in productivity at work, a closing-off of new opportunities, a reduction in quality of life, a possible deterioration in general health and possibly preventable blindness.

We want to end this.

The scale of the problem is massive - the World Health Organization has pinpointed refractive error (the technical term for improperly corrected vision) as the number one cause of low vision in the world today, and the second greatest cause of preventable blindness after cataracts. Estimates place the number of people who need vision correction and lack it at well over one billion.

The problem is set to get worse, as epidemiological studies have determined that refractive error is on the rise as the populations of developing nations become more urban. Increasing life expectancy will also cause an increase in the number of people who will suffer from presbyopia - the inability to focus on close objects, requiring reading glasses.

Using the World Health Organization's recommended measure of a health issue's effect (the Disability Adjusted Life Year), refractive error will rise into the top ten global health issues affecting productivity and opportunities by 2030, passing HIV/AIDS in its global burden.

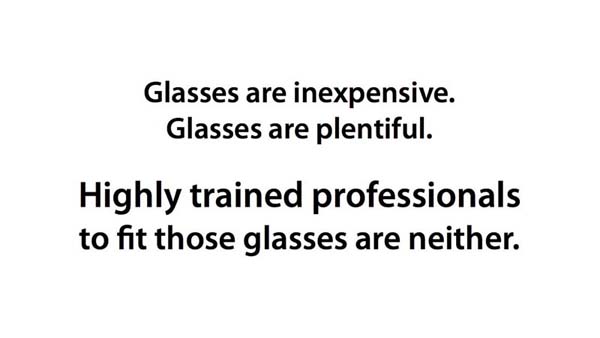

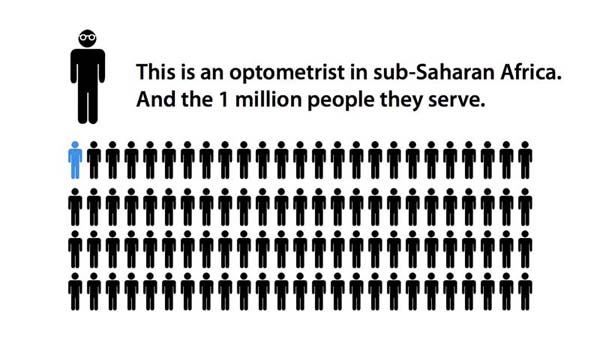

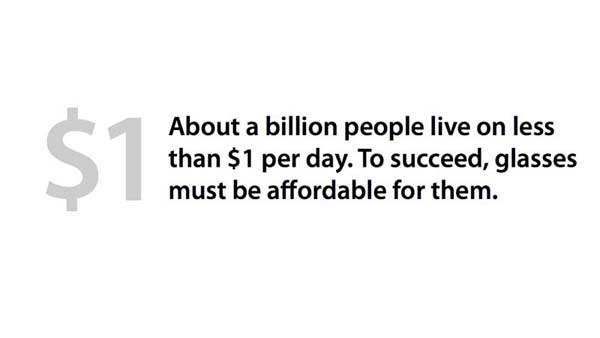

The greatest barrier to effective treatment is a lack of trained optometrists. Many developing nations have as few as one optometrist for every million of the population. (For comparison, the figure in the UK is around 1 per 8,000.) A lack of dedicated facilities and equipment also limits access to eyecare. Compounding this issue, the cost of traditional eyewear is prohibitive for the many people surviving on less than one dollar per day.

Current methods of solving this issue have proven ineffective; a new approach must be found.

Research Publications

Published Papers

Optician

Global cost of poor vision

Global cost of poor visionJ. D. Silver, The Optician (2013)

British Medical Journal

Self correction of refractive error among young people in rural China: results of cross sectional investigation

Self correction of refractive error among young people in rural China: results of cross sectional investigationM. Zhang, R. Zhang, M. He, W. Liang, X. Li, L. She, Y. Yang, G.E. MacKenzie, J. D. Silver, L. Ellwein, B. Moore, N. Congdon, BMJ (2011)

Ophthalmology

The Child Self-Refraction Study - Results from Urban Chinese Children in Guangzhou

The Child Self-Refraction Study - Results from Urban Chinese Children in GuangzhouM. He, N. Congdon, G.E. MacKenzie, Y. Zeng, J.D. Silver, L. Ellwein, Ophthalmology, Vol 118 (2011)

Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics

Self-optimised vision correction with adaptive spectacle lenses in developing countries

Self-optimised vision correction with adaptive spectacle lenses in developing countriesM. G. Douali and J. D. Silver, Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, Vol 24 (2004)

South African Optometrist

How to use an adaptive optical approach to correct vision globally

How to use an adaptive optical approach to correct vision globallyJ.D. Silver, M.G. Douali, A.S. Carlson and L. Jenkin, South African Optometrist, Vol 63 (2003)

International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness

Vision correction with adaptive spectacles

Vision correction with adaptive spectaclesG. D. Afenyo and J. D. Silver, in World Blindness and its Prevention, vol. 6, ed. Pararajasegaram and G. N. Rao, p. 201-208 (International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, 2001)

Posters and Presentations

Second Oxford Conference on Vision for Children in the Developing World

An Introduction to Self-RefractionJ.D. Silver

American Academy of Optometry, October 2011, Boston

The Boston Child Self-Refraction Study

The Boston Child Self-Refraction StudyB., OD, C., OD, S. Lyons, OD, N. Quinn, OD, P. Tattersall, DipPharm, MSc, J.D. Silver, Dphil, D.N. Crosby, DPhil, M. He, MD, L. Elwein, PhD, G. MacKenzie, Dphil, N. Congdon, MD

Vision UK 2009, London

Estimating the Global Need for Refractive Correction

Estimating the Global Need for Refractive CorrectionJ.D. Silver, D.N. Crosby, G.E. MacKenzie, M.D. Plimmer

Adaptive Optics 2008, London

Vision Correction in the Developing World: Perhaps the largest application of Adaptive Optics?

Vision Correction in the Developing World: Perhaps the largest application of Adaptive Optics?D.N. Crosby, M.G. Douali, G.E. Mackenzie, M.D. Plimmer, R. Taylor, J.D. Silver

IAPB 8th General Assembly, Buenos Aires

The Global Need for Refractive Correction

The Global Need for Refractive CorrectionJ.D. Silver, D.N. Crosby, M.G. Douali, G.E. Mackenzie, M.D. Plimmer

ICEE World Conference on Refractive Error and Service Development, Durban

Repeatability and reproducibility of self-refraction using continuously adjustable fluid-filled spectacle lenses in pre-presbyopes

Repeatability and reproducibility of self-refraction using continuously adjustable fluid-filled spectacle lenses in pre-presbyopesG.E. Mackenzie, J.D. Silver, D.N. Crosby, M.J.A. Newbery, A.K. Robertson

Conferences

March 2011 - BMJ Innovation Expo

Panel discussion:The panel identified Josh Silver's self-adjustable glasses as the idea most likely to make the biggest impact on healthcare by 2020.

April 2011 - Second Oxford Conference on Vision for Children in the Developing World

Conference Aims:The Conference then explored the potential for the wider application of self-refraction using adjustable spectacles and other appropriate vision technologies to children in the developing world and agreed next steps for further development.

July 2007 - Vision for Children in the Developing World

Conference Aims:Representatives from the scientific community, donors, NGOs and the private sector will review the need for the provision of affordable vision correction to children across the developing world, review sustainable protocols for the collection, analysis and dissemination of refractive data and propose an action plan to implement key recommendations.

August 2004 - Affordable Vision Correction Conference

Conference Aims:This conference aims to gather representatives from governments, NGOs, faith-based organizations and the private sector to discuss different approaches for the provision of vision correction across the world as well as to identify and review the options available.

Lens Technology

This page contains information on various adjustable (or adaptive) lens technologies that are suitable for application to spectacles for the developing world.

Click through the tabs below to discover more about adjustable lens technologies.

The Eye - the original adjustable lens

Our eyes incorporate a flexible lens (the crystalline lens) - it allows us to change our focus to far or near objects (accommodation). The lens is surrounded by a ring muscle (the ciliary muscle), which relaxes to allow the lens to flatten or contracts to cause the lens to bulge, changing its refractive power.

Problems

Unfortunately, there are a number of conditions that the eye can suffer from. Most people will suffer as their lives go on from presbyopia - a loss of ability to change the power of the lens due to hardening of the lens tissues, leading to a lack of ability to focus on close objects, such as when reading.

Other common conditions that affect large numbers of people are:

- Myopia: (short-sightedness) Rays of light from a distant object are focussed in front of the retina. Myopia occurs either because the eye is too long or the refractive elements (the cornea and crystalline lens) too powerful to produce a clear image at the retina.

- Hyperopia: (long-sightedness) Rays of light from a distant object are focussed behind the retina, either because the eye is too short or because the refractive elements of the eye are not powerful enough to bring an image into focus at the retina.

- Astigmatism: Astigmatism occurs when the curvature of any given refractive element of the eye differs across its surface (i.e. the lens in the eye is shaped more like a rugby ball than a football). This lack in uniformity across the surfaces of the eye's refracting elements prevents it from producing a sharply focused image at the retina. Astigmatism usually produces an image that is more defocused in one direction than another.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does CVDW do?

The Centre for Vision in the Developing World studies the clinical and practical issues in providing vision correction to people who currently lack access to it. We research and develop effective, sustainable and clinically-validated approaches to the correction of refractive error in developing world populations.

What is CVDW's position on self-adjustable glasses?

We have a strong research interest in self-refraction and self-adjustable glasses, and we believe they are an effective way to tackle the lack of access to vision correction in the developing world.

Does CVDW distribute adjustable glasses?

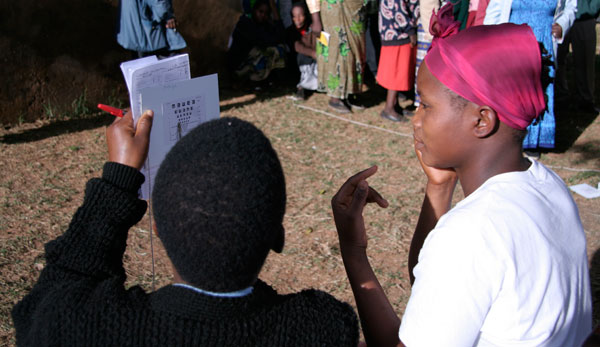

As part of our research studies and clinical trials, we undertake distributions in the developing world.

Am I able to buy a pair of adjustable glasses?

At present, CVDW supplies adjustable glasses only to its developing world distribution partners and to researchers for the purposes of clinical and field trials.

What conditions do the adjustable glasses treat?

Adjustable eyeglasses are designed only to work for the same conditions that normal eyeglasses work for. They do not prevent or reverse macular degeneration or any ophthalmic condition other than spherical refractive error (myopia and hyperopia; also presbyopia).Refraction Methods

The developing world has a number of different requirements for refraction methods compared to the developed world, for reasons including primarily the lack of trained optometrists, but also transportation difficulties, the scale of the issue, requirements imposed by a low level of education in many places and a lack of facilities and money.

Click through the tabs below to discover more about refraction techniques.

Subjective Refraction

Subjective refraction is the traditional refraction technique used by optometrists around the world. The process works by adjusting a corrective lens placed on the patient and querying the patient on how the changes affect their vision, using a variety of observation charts. From determining where a patient can read to on a visual acuity chart (either a 'letters' chart, or a split C or rotated E chart), this method is also used to determine a patient's visual acuity (e.g. 20/20 vision).

Subjective refraction is the traditional refraction technique used by optometrists around the world. The process works by adjusting a corrective lens placed on the patient and querying the patient on how the changes affect their vision, using a variety of observation charts. From determining where a patient can read to on a visual acuity chart (either a 'letters' chart, or a split C or rotated E chart), this method is also used to determine a patient's visual acuity (e.g. 20/20 vision).

The process has been used and refined over many years, and achieves a high degree of accuracy statistically. The Centre has conducted work into examining the reproducibility of the refractions obtained through this method at UK optometrists, which can be found on our Research Publications page.

Subjective refraction has the advantage of being able to determine both sphere and cylinder (astigmatism) corrections, as well as being able to determine (with appropriate training) common eye diseases as part of the examination.

Applicability to the developing world

Subjective refraction, although the ideal solution for nearly everyone requiring corrective aids to vision, is currently difficult to practice in the developing world and would be unable to correct the one billion people who need vision correction. The technique is unsuitable for a number of reasons:- It requires trained optometrists undertaking one-on-one screenings: there are currently far too few optometrists in the developing world, and healthcare costs put them out of reach of most of the population.

- The capital costs of training and equipping an optometrist are very high, prohibitive for many.

- Dedicated facilities are often required in the form of vision clinics and practices.

- Language and communication difficulties can often arise in the process, especially if the optometrists are not from the local area or nation.

Correction Methods

Click through the tabs below to discover more about correction methods.

Traditional Eyeglasses

In the developed world, eyeglasses are usually obtained through optometrists' practices, and the correction prescription they determine through subjective refraction is sent to an optical laboratory, where lenses are ground to the correct refractive power and cut to the correct shape to fit into frames.

In the developed world, eyeglasses are usually obtained through optometrists' practices, and the correction prescription they determine through subjective refraction is sent to an optical laboratory, where lenses are ground to the correct refractive power and cut to the correct shape to fit into frames.

In many parts of the developing world there are difficulties with this approach; suitably trained professionals are needed to measure the prescription required and optical laboratories are expensive to set up and run. Neither of these are available in anything like the number available to meet the current need. Facilities that do exist are usually located in major cities meaning that the cost of access for many individuals, given the time and travel required, can also be prohibitive. As such although this approach can be effective, it is often beyond the reach of all but the wealthiest.

The challenge is to find an appropriate solution that will scale and perform well for the vast numbers of people lacking vision correction worldwide.

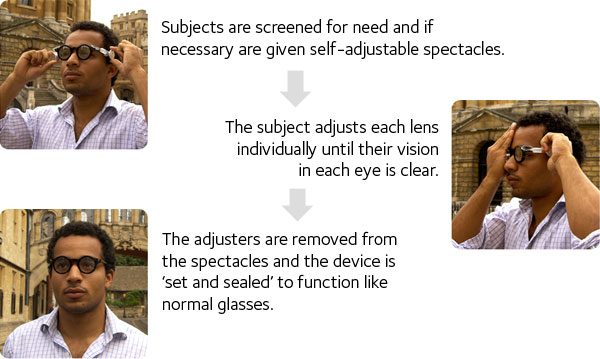

Adjustable eyeglasses (also known as adaptive eyewear or adaptive glasses) get around the problem that faces many correction techniques by being a single (or very few) unit(s) that can be changed in the field to produce a range of different prescriptions, without needing additional parts or labour.

Adjustable eyeglasses (also known as adaptive eyewear or adaptive glasses) get around the problem that faces many correction techniques by being a single (or very few) unit(s) that can be changed in the field to produce a range of different prescriptions, without needing additional parts or labour.

Contact lenses are a common form of vision correction in the developed world for certain conditions, used by many millions the world over every day.

Contact lenses are a common form of vision correction in the developed world for certain conditions, used by many millions the world over every day.